The Power of the Placenta

The placenta is more than the MVP in pregnancy—it’s a lifeline.

Medical Expert: Lauren Demosthenes, MD, OB-GYN

From the moment of conception, your body begins preparing to accommodate your growing fetus. In healthy pregnancies, often before you even know you’re expecting, developments are underway to create a safe, watery world inside the womb that provides a new embryo with everything needed to continue to thrive. One of the most important developments is the placenta, a temporary organ that connects to the fetus through the umbilical cord and delivers oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and even immunities that can provide protection.

Also referred to as “afterbirth,” the placenta is made with cells from both the birth parent and the fetus. The placenta develops from the fertilized egg, making it genetically half of each parent, plus contributions from baby. This joint effort results in the creation of an entirely new organ, a disk that generally measures 8 inches in diameter and weighs about a pound by delivery day. While the placenta continues to grow throughout pregnancy, it “takes over” hormone production around 12 weeks gestation, or toward the end of the first trimester. Up until that point, the corpus luteum, another temporary organ that generates progesterone, handles most of the hormone production. It’s thought that many people’s first-trimester symptoms of nausea and fatigue improve once the placenta takes over in the second trimester.

While pivotal, powerful, and pretty amazing, the placenta is also shrouded in mystery and considered by scientists as one of the least understood organs in the human body. Researchers do know that abnormal placental development can cause complications in pregnancy, including poor fetal development, preeclampsia, and stillbirth. But don’t worry, your health care provider will monitor for red flags in placental development throughout your pregnancy. Additionally, there are ways you can improve your chances of having a healthier placenta and a healthier pregnancy and birth.

Primary Functions of the Placenta

There are three main purposes of the placenta: to deliver oxygen and nutrients to the fetus, to remove harmful waste from its bloodstream, and to provide the necessary hormones for fetal growth. The placenta keeps your unborn baby alive and helps to prime them for survival outside the womb, acting as their lungs, liver, and kidneys until birth.

Deliver oxygen and nutrients

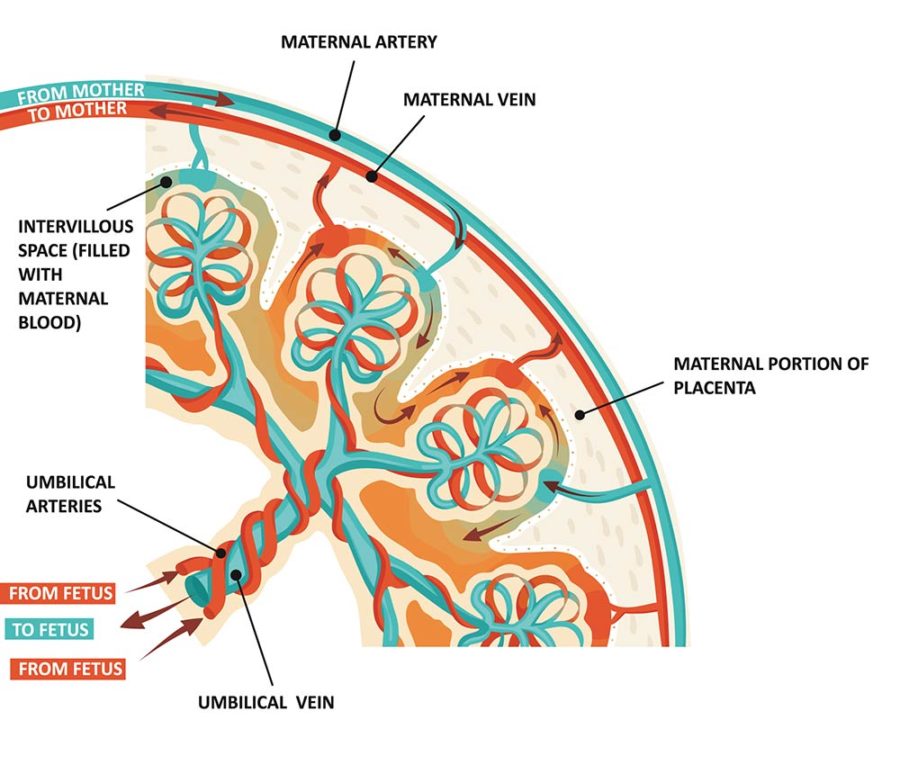

A developing fetus doesn’t eat or breathe and relies solely on the birth parent for nourishment and oxygen. The birth parent’s blood passes through the placenta and provides oxygen, glucose, and nutrients to the baby through the umbilical cord, essentially acting as one giant straw for the fetus.

Remove waste

Just like life outside the womb, your baby takes in oxygen and releases carbon monoxide in utero. The placenta works as a filter, keeping baby safe from harmful gas and other waste products, including urea, uric acid, and bilirubin, to be disposed of through the maternal blood circulation. What’s equally impressive, the placenta enables this exchange of oxygen and nutrients between your and your baby’s bloodstreams without ever mixing them.

Provide essential hormones

The placenta produces a host of important hormones during pregnancy that contribute to the well-being of the pregnant person and their developing baby.

- Human chorionic gonadotropin hormone (hCG): This hormone is what pregnancy tests detect and is thought to play a part in early pregnancy morning sickness. It is found in a pregnant person’s blood and urine.

- Human placental lactogen (hPL): This hormone gives nutrition to the baby and stimulates milk glands in the breasts for breastfeeding after birth.

- Estrogen: Typically only made by the ovaries, estrogen is also created by the placenta and helps maintain a healthy pregnancy.

- Progesterone: Also split between the ovaries and placenta for production, progesterone (responsible for stimulating the thickening of the uterine lining for implantation of the embryo) is created to continue supporting the womb.

When needed, hormonal supplements can be used to maintain growth and development until the placenta is fully formed, explains Lauren Demosthenes, MD, OB-GYN, senior medical director at Babyscripts, a virtual maternity care platform. For example, “If a pregnancy is the result of reproductive technology, such as IVF, a person will be given hormonal supplements until the placenta can take over [hormone production], which happens around 12 weeks.”

Once the placenta is fully formed, it holds the power to dictate the trajectory of the remainder of the pregnancy.

How the Placenta Impacts Pregnancy and Birth

Location of where the placenta implants can affect a pregnancy and how a baby needs to be safely delivered. The placenta can form anywhere in the uterus and develops wherever the fertilized egg implants into the uterine wall—front, back, right, or left. According to the Cleveland Clinic, the placenta’s positioning can change up until 32 weeks of pregnancy and is likely to move upwards and away from the cervix as baby grows, though any of the following formations are possible:

- Posterior placenta: The placenta attaches to the back of the uterus.

- Anterior placenta: The placenta attaches to the front of the uterine wall (closest to your abdomen).

- Fundal placenta: The placenta attaches at the top of the uterus.

- Lateral placenta: The placenta attaches to the right or left wall of the uterus.

- Low-lying placenta: The placenta attaches to the lower area of the uterus.

While some of these positions come with undesirable consequences, such as not being able to feel your baby’s kicks as easily or difficulty locating a fetal heartbeat during prenatal appointments, they do not always equal dangerous outcomes. However, there are certain conditions where the placenta embeds too deeply into the uterine wall, which can lead to difficulty removing the placenta after birth, dangerous bleeding, and even loss of the uterus.

- Placenta accreta: This occurs when the placenta attaches itself too deeply and too firmly to the uterine wall.

- Placenta increta: This refers to the placenta attaching to the uterine muscle beyond the wall.

- Placenta percreta: This is where the placenta goes completely through the uterine wall, sometimes extending to nearby organs, such as the bladder.

These conditions happen in about 1 in 530 births each year, and according to Dr. Demosthenes, complications are more common in patients with a previous C-section or uterine surgery, such as a fibroid removal.

Placenta previa is a separate condition where the placenta is below the cervix and partially or fully blocks the cervical opening, interfering with a vaginal delivery. “There is no way to move the placenta if this happens,” says Dr. Demosthenes. This often results in the need for a cesarean and affects approximately 1 in 200 pregnancies.

Other complications include placental abruption, when the placenta separates too early from the uterine wall, and placental insufficiency when the placenta fails to thrive. Both of these conditions may be caused by high blood pressure or the use of substances like nicotine and drugs. Placental abruption can also result from physical abdominal trauma, such as in a motor vehicle accident or a fall.

“This is why a good health history and prenatal care is important,” notes Dr. Demosthenes. “The health care team can be on the lookout for situations that might increase the [placental complication].” Additionally, she says ultrasound and fetal monitoring may be needed to monitor the baby’s health for the duration of the pregnancy.

Factors of Placenta Health

A healthy placenta continues to grow and function throughout a pregnancy and is then delivered intact shortly after birth. Like other aspects of pregnancy, placental development can be impacted positively or negatively by lifestyle choices.

“A healthy placenta can be achieved by a healthy lifestyle,” says Dr. Demosthenes. “This includes mindful eating, taking prenatal vitamins, and avoidance of unhealthy substances like alcohol, nicotine, and even certain medications that may be harmful to the baby. Medications that cross the placenta and get to the baby should be discussed with the health care team.”

The phrase “cross the placenta” refers to substances transferring from the birth parent to the baby. The placenta is not a perfect barrier from harmful substances, including certain medications, drugs, alcohol, and nicotine.

“Lots of things—good and bad—cross the placenta and can affect the baby. Alcohol, nicotine, and many medications cross the placenta and can have a negative effect on the baby, such as stillbirth, preterm birth, and growth problems,” warns Dr. Demosthenes, adding, “But good things can also cross the placenta like antibodies that will protect the baby. Viruses can cross the placenta as well, and maternal vaccinations can help prevent this from happening.

“Additionally, certain medical conditions can negatively affect the placenta, like high blood pressure and diabetes. The placenta has a lot of blood vessels that carry the nutrients and oxygen [to the baby], so conditions that affect the blood vessels, in general, can affect the placenta,” she explains.

According to the Mayo Clinic, various additional factors can affect the health of the placenta during pregnancy, including:

- Maternal age

- A break in your water before labor

- High blood pressure

- Twin or multiples pregnancy

- Blood-clotting disorders

- Past uterine surgery

- Previous problems with the placenta

- Substance use

- Abdominal trauma

It’s important to note that pregnancy is not a one-size-fits-all scenario. Every person’s experience is different and comes with its own unique set of challenges. As stated before, having prenatal care and a provider you feel comfortable discussing concerns with is key to navigating the prenatal process and achieving the best possible outcome.

The Placenta Post-Birth

If you deliver your baby vaginally, you will also deliver the placenta vaginally, usually within 30 to 60 minutes after birth. You will continue to experience mild contractions and may be asked to push again as your body expels the placenta. During a C-section delivery, your care provider will remove the placenta as part of the procedure.

Once delivered, your provider will examine the placenta and determine if it’s fully intact. If fragments are remaining in the body, they must be promptly removed from the uterus to prevent bleeding and infection. And while you might assume at that point that the placenta’s work is finished, that’s not always the case.

“The placenta is delivered after birth but can still serve a good function,” says Dr. Demosthenes. “Some people will have the placental blood collected (aka the cord blood) and will store the stem cells which may protect against disease and life-threatening conditions in the future.” Certain cultures opt to take the placenta home and bury it in a special place, such as in a backyard garden or mark the burial with a newly planted tree. There are also services to turn your placenta into art prints, tinctures, teas, salves, dried keepsakes, and more.

“Some people eat their placentas or form capsules from the placenta to help with various conditions like postpartum depression and breastfeeding,” adds Dr. Demosthenes, noting, “There are no studies to confirm that this works, but there are studies that have shown toxic effects from viruses, bacteria, and heavy metals in the placenta that even encapsulation cannot prevent. Therefore, eating the placenta and encapsulating it is not recommended, in general.”

Whatever the ending looks like, the life of the placenta is nothing short of incredible. And the fact that your body orchestrates it all speaks to your amazing power, too.