Why I’m a Better Father than my Fathers

I had one mission when I became a parent: to be the person I needed in childhood.

Parenthood has set me on a path of healing, but it was a slow, painful crawl to get here. Though my story is always (thankfully) evolving, my past makes up the foundation of my present, and I’m learning to draw the good from it while building something better.

I was born into a very conservative family. My mom was 18 years old when she became pregnant, and the only options she was given were to either give me up for adoption or marry my biological father. A family had already been selected to take me once I was born, but ultimately my mother decided to keep me and agree to marriage. I think it’s really unfortunate that those were the only options she felt she had, and ultimately my parents divorced a year after I was born.

My mother is incredible. I was very close to her growing up while living with her and my grandmother. My biological father was pretty absent. He would come to a few family gatherings here and there, but after a few years, I never saw him. Throughout adulthood, I made attempts to start over, not as father and son, per se, but as two people who share DNA and should know one another because life is short and no one is perfect. But we do not have a relationship.

I grew up with plenty of “father figures” since my mom was young and dated a lot. I was incredibly envious of all my friends who had dads. From baseball games to camping trips to school events, I’d often be joined by whoever my mom was dating at the time, but I never had a real dad.

My mother remarried when I was 10. I didn’t like the guy much. He was very cold and always seemed annoyed with me, his inherited son. During their wedding I almost stood up and expressed my opposition to their union, but I ultimately chickened out. To this day, I wish I had made my reservations known, but you know … I had dad issues, and I often reverted to people-pleasing to get my needs met.

After their wedding, they went on a summer-long honeymoon while I stayed with my grandmother, who I had been living with for 10 years. As a child, I couldn’t comprehend the changes that were happening, and I assumed that I would continue to live with my grandmother while my mother visited periodically. I was heartbroken when I realized that I would be moving to a new home and living under the authority of my mom’s new husband.

In addition to constantly feeling like I had to prove myself, I also learned to believe that I was undeserving. This lie was characteristic of my adolescence: My parents spent $80,000 on a new kitchen but left my room with incomplete renovations (we’re talking gaps in the walls, no trim, stripped paint, etc.) that weren’t finished until I moved out; when invited to social gatherings like friends’ birthday parties or a group movie night, I was told if I couldn’t pay for a gift or a ticket that I couldn’t go. Sometimes money would be advanced to me, but a record of debt was always kept; I recall a Christmas where my gift was a card forgiving me of my debts for that year. This dynamic fortified the narrative that I was not safe and should not expect anything in life. What’s more, they actively discouraged me from spending time with my biological father’s parents, who I loved very much.

Her husband adopted me when I was 11. I wasn’t told much about why it was happening or why my last name was changing. When I asked about the adoption, my soon-to-be stepfather said something like, “It’s so when I die the government won’t be able to take all my money.” One vivid memory I have of the adoption proceeding was the judge stating, “The child’s father was given the opportunity to appear but has not responded to the court.” That was one of the saddest moments of my life. My dad didn’t even care enough about me to show up and fight for me as his only child. He just let someone else have me; just like that, like I was nothing.

After the adoption, my new dad gave me a fancy watch to commemorate the occasion, something that was likely instigated by my mother. He bought a matching one for himself. It was supposed to be sentimental, but I pawned it for $40 a few years later. That’s sort of how our relationship stayed.

As you may imagine, my teens and twenties were really rough. Like many kids with parental wounds, I did all the wrong things to try and feel loved and accepted, not knowing how to advocate for myself. I won’t get into all of the details, but let’s just say I got into a lot of trouble, and I am extremely fortunate to be alive.

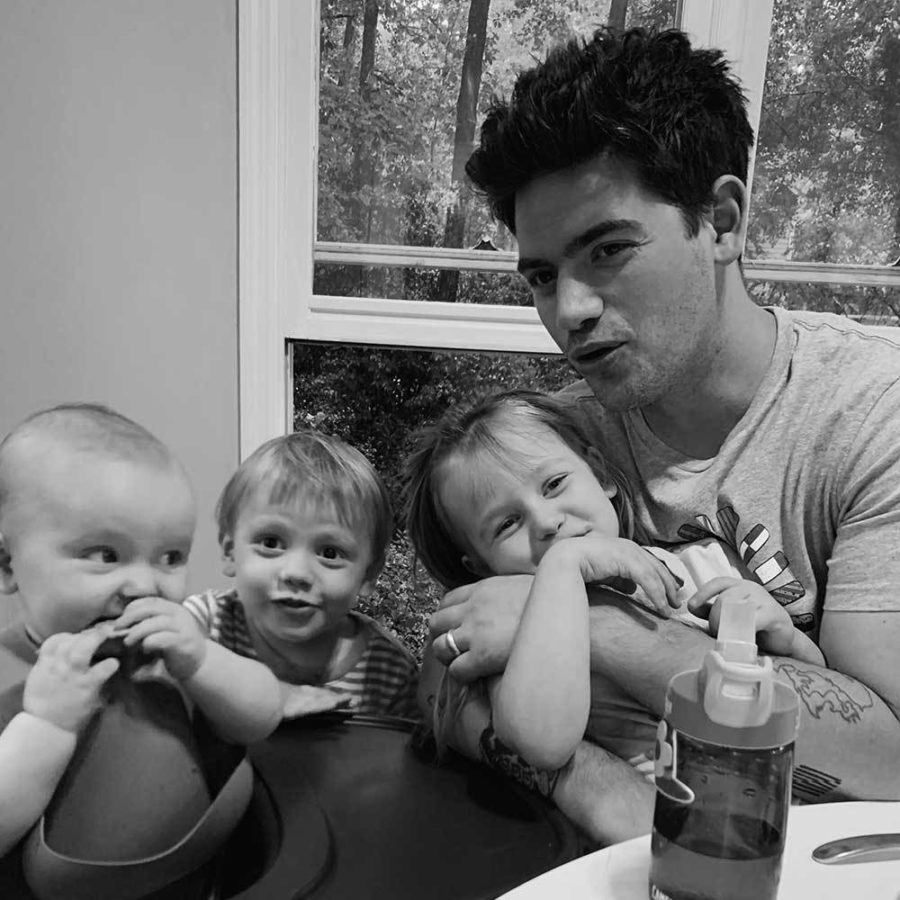

In my mid-twenties I met my wife, fell in love, got sober and started moving forward in life. By the time I was 30 we had two children a year apart, and then we went on to have two more shortly after. I’m now 35, have been married for eight years and am the father of four, ages 5, 4, 18 months and 6 months.

From the moment my firstborn entered the world, I just wanted to be a better dad than the ones I had. At first, I honestly felt like I had this in the bag as if it would be so easy to be a better father. But some days I felt—I feel—like an awful parent. Having four little kids is hard, and I see evidence of my past—and the influence of my fathers—creeping into my daily parenting.

Once I realized I couldn’t continue to stuff the hurt from my past, I decided to let it out, and stare it face down.

I Chose to Confront my Trauma

One of the best decisions I’ve ever made was to seek help from a professional. I’ve been in therapy for the last three years trying to understand what happened to me when I was a child, how and why those events have influenced my thoughts and actions, and how to change the narrative moving forward. This is where I’ve landed on the subject of fatherhood (and pretty much everything else in life): You have to be able to love yourself.

Hang with me for a second and try to think of someone in your life who loves themselves down to their core, well beneath the surface. How do they act? What words come out of their mouth? Now think about someone who may struggle to love, or even accept themselves. How do their words and actions differ? My therapist reduced this theory once to simply: Good in, good out. Bad in, bad out. It’s extremely uncomfortable to peel back the layers of myself and rebuild alongside a therapist, but it’s been fruitful. I know I am reaping the benefits of vulnerability and honesty.

There’s this architecture in life that you can see everywhere: rivers flowing, branches growing, veins pumping—things projecting from their sources. If you love yourself, your children will be loved. The essence of your heart will flow out to those around you. It works both ways though. That’s why you have to do what’s hard (i.e. get the bad stuff out of your heart) and make sure your children’s inheritance isn’t baggage from whatever you hated about your parents. Great change requires great action.

And that’s the step I took … and the stairwell I’m trying to climb. I definitely have some rough days; I don’t always get it right, but I’m learning to love and have compassion for myself because I needed that as a child. I’m trying to do the work. The kind of work that maybe my parents’ generation didn’t have the opportunity to do. I want to be a good dad. I want my kids to feel secure. I want them to be filled and see a world of possibilities, to see the potential in other people and most importantly, in themselves. I don’t want my kids to need a therapist to believe that they’re good enough or to know their inherent value. I’m healing my inner child so that my children can love themselves effortlessly. That’s the inheritance I hope to leave them.

I Chose to Be Present Over Perfect

There’s a lot of stigma around masculinity and fatherhood. I was raised without seeing a healthy output of emotion while also thinking that dads fulfill certain roles in the home, including the financial provider, the “fun” parent, the stoic one with the final say on decisions, etc. These are the things that make a “real man.” Though I was primarily raised by women, I still had some deconstructing to do in adulthood because of these societal expectations.

I want to say that there’s nothing strange about a father being involved with the ins and outs of his family life. What is strange to me is a man with a family being considered a “family man” for shouldering basic parental responsibilities. While perhaps less common, it’s not weird for the fathers of our generation to stay home with their kids or be the one to change a diaper at a restaurant or be the one apologizing during your Zoom meeting because your toddler makes a cameo.

My wife and I share parenting 50/50. We both tackle feedings/meals, and do (tons) of laundry, and most importantly, try to meet the dynamic needs of our kids. Men can—and should—reject the notion of merely being a babysitter. A father’s role is irreplaceable, and his influence runs deep.

While difficult (every single day), I try to make myself emotionally available to my kids. Like all children, they have a lot of confusing feelings, a lot of outbursts, and a lot of questions. I try to listen to them, look them in the eye, and validate their words. I say “sorry” a lot. I explain that I am also trying to better understand my emotions, and that I am responsible for how I handle my reactions. It’s very humbling. Being present means they see me working out my shortcomings in real-time, but at least they see me.

My father-in-law is a great man, but he will admit he spent many weekends hunting or fishing after being gone all week for work. He’s pulled me aside teary-eyed more than once to say, “You’re doing it right. You will never regret being here for this time. I wish I could go back and make different choices.” While regret is not something I encourage, I think hindsight is valuable—I know mine has been.

I bring all this up in an attempt to normalize any father feeling unsure of his place, or questioning who he is, or wondering if he’s screwing it all up. (All parents worry about that one.) No matter what your father was like, you can be whatever father you want to be. There are steps you can take and people who will support your efforts. Success in therapy is just my experience and how I personally found a way to make some peace with my past and move forward.

My hope is that society embraces men prioritizing their mental health and choosing to change generational ideals that have been damaging. While I can’t be the official judge of whether or not I am a better father than my fathers, I know I am actively pursuing being a good father, and I have to trust that that’s enough.